- Starring

- Gabriele Ferzetti, Monica Vitti, Lea Massari

- Writers

- Michelangelo Antonioni, Elio Bartolini, Tonino Guerra

- Director

- Michelangelo Antonioni

- Rating

- n/a

- Running Time

- 144 minutes

Films such as Schindler’s List and 12 Years A Slave are often referenced as effective filmic social commentaries. Rather than being socially reflective, it could be argued that these films are socially exploitive; they display the horrors of life, allowing them to be discussed and scrutinized, and exposing little known or commonly taboo topics. Socially reflective cinema does not focus on a particular society’s norms, attitudes, or beliefs as the subject of the film, rather it is that society’s experience that is deeply meaningful in informing the purpose behind the film.

Socially reflective cinema was revolutionized in the 1960’s and ushered in with a new era of filmmakers and thinkers such as, Verda, Godard, and Truffaut. During this era of new wave thinking and change in filmmaking, the Italian neorealism movement began to fade as most filmic scholars began to turn their focus from the Mediterranean to Continental Europe. Although many choose to ignore the ensuing wave of cinematic thought from Italy, a new film movement, Post-neorealism, had emerged. The first film in this new-guard of Italian cinema, was Michelangelo Antonioni’s medium-defining and highly influential film, L’Avventura.

This film not only stands on its own as a captivating, ambitious story about love and loss, but also acts as a satire on Italian film, as well as a socially reflective commentary on the effects of the two World Wars on Italy, and the widespread social change occurring across the country. Through various storytelling and satirical techniques, L’Avventura serves as a social and political allegory for the disillusioned post-war state of Italy’s infrastructure, people, and artistic culture.

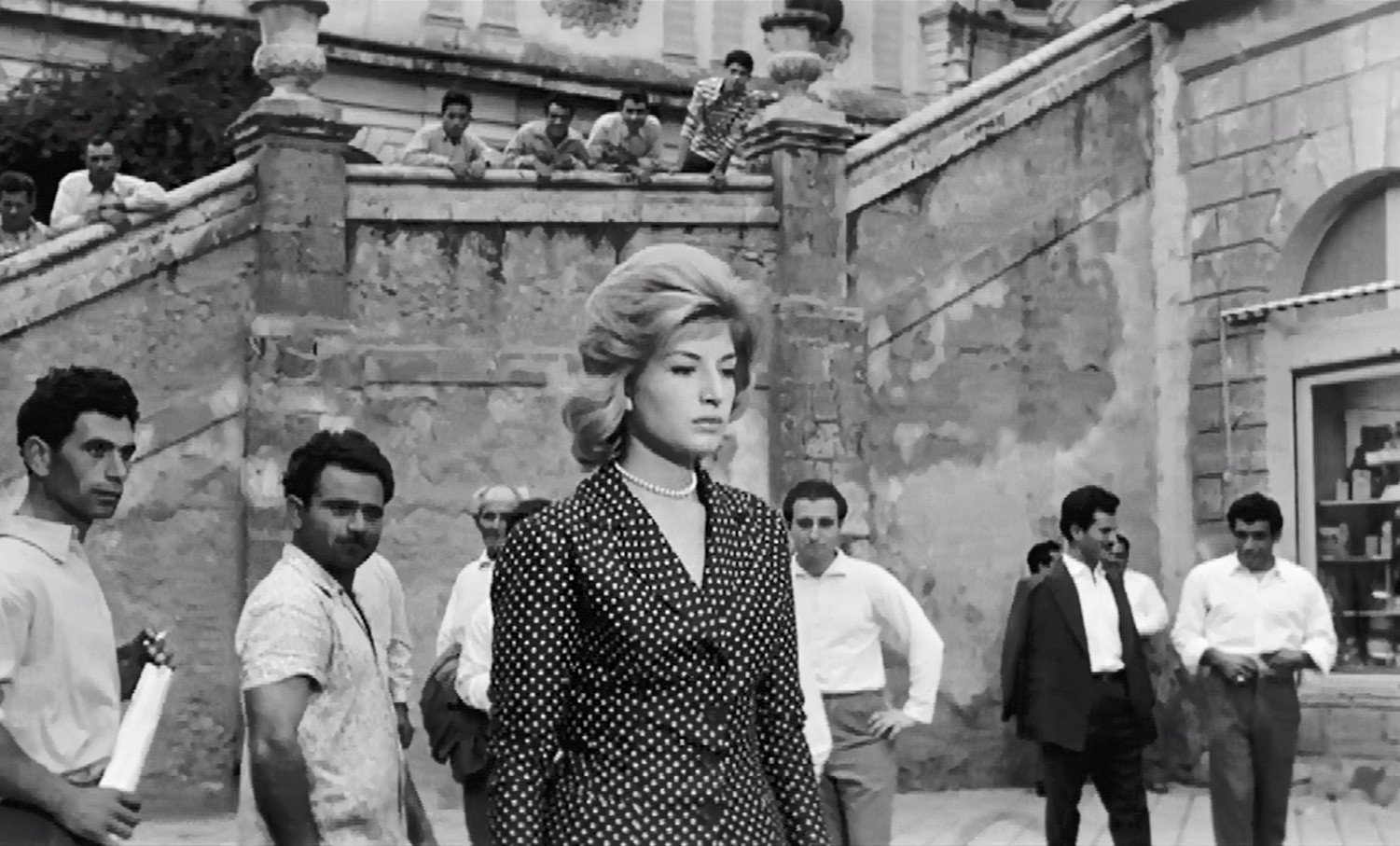

The most commonly discussed aspects of L’Avventura are the storytelling, overall plot, and the unusual ending. The film surrounds three leads: Sandro, his girlfriend Anna, and their mutual friend Claudia. Anna goes missing after a group trip to an island off the coast of Italy. Claudia and Sandro find themselves searching for Anna, until they stop searching and find each-other, starting a whirlwind romance, which almost completely leaves Anna out of the rest of the film. Anna’s fate is never revealed, nor is it needed, as the remainder of the film is focused entirely on Claudia and Sandro’s romance. Anna, feeling an overwhelming sense of misery and gloom, complains to Sandro throughout the island trip. Following her disappearance, Claudia spends most of the remainder of the film feeling much the same way.

This sense of isolation and depression felt by both female leads is a common element within most of Antonioni’s work, and resulted in L’Avventura, along with its two consecutive follow-ups (L’Eclisse and La Notte), being referred to as the isolation trilogy. In L’Avventura, this sense of isolation acts as an allegory for the social disenfranchisement of Italians. As historian Klaus F. Zimmermann states, “Italians emigrated mostly towards Europe, especially Germany. In the same years, the development of the industrial north stimulated mass internal migration from the south to the north west.â€

The economic and industrial boom in the north of Italy led to many southern Italians being left behind in a state of abject poverty and rampant crime. These themes were reflected in many films of the time, predominantly from the Italian Neo Realism movement, an example of which is Bicycle Thieves. It can be extrapolated that this disillusionment with their nation would have resulted in southern Italians experiencing a great sense of isolation, mirrored by the isolation and depression of the characters within L’Avventura. Anna’s disappearance can be seen as a metaphor for the mass emigration that took place following the two World Wars, and her eventual disappearance from the storyline, as Sandro and Claudia forget about her, as a comment on how Italy as a country left many of its own behind.

Another important film to the culture of Italy in the post-war era was the aforementioned Bicycle Thieves. This Italian Neo Realist film swept the national sentiment along with it, in a beautifully told story about an impoverished man whose bicycle is stolen, preventing him from working, and eventually, after hours of searching, turning to stealing in order to right the situation. The film spoke to those who were disenfranchised by Italy’s involvement in the war, who felt as if they had been left behind and forgotten. Bicycle Thieves depicts the poverty in Italy through an early sequence in the film, in which the lead sells his bed sheets in order to afford repairs to his bicycle. This film, and its ilk, depicts Italians in their impoverished state resulting from World War II. In contrast, L’Avventura and most of Antonioni’s films focus on those of great wealth, and therefore satirize Neo Realism, while making the same statement.

Throughout L’Avventura, the characters are struck by a strange, ongoing, unidentifiable sense of depression and sadness, which is not instigated by any particular event. The characters’ constant depression is often juxtaposed with the mise-en-scene of the film: Anna is severely depressed while sitting on a luxury yacht, and Claudia has moments of extreme sadness while staying in a five-star hotel, or walking through a grand ballroom. Their sadness is juxtaposed with lavish surroundings, counterposed to Italian Neo Realism, in which characters’ sadness is reinforced by crumbling cities and visible poverty. L’Avventura excludes southern Italy, being shot entirely on location in Central and Northern Italy to showcase the harsh industrial architecture of these regions, something Antonioni delves further into in La Notte, as well as the desolation of the barren islands off Italy’s coast, which are on display for most of the first half of the film.

Interestingly, the setting of the island can also be understood as a comment on the isolation and disenfranchisement of Italians. It is significant that while Anna, as indicated earlier, expresses her isolation and depression while on board the yacht, she does not disappear until she arrives on the island. Antonioni is poking fun at the overtly realist approach to filmmaking in Neo Realism while on the yacht, then is critiquing the upper class and commenting on the general Italian sentiment while on the island.

This ‘Italian Cinema of the North’, as it could be referred to, exemplifies how even the bourgeoisie of Italy search for meaning they will never find. It unifies the country: Neo Realism, showing how the impoverished search for meaning out of their reach, that they believe the rich to possess, and how the rich search for a meaning they do not fully understand and therefore can never possess. Post-Neo Realism is a farce of Neo Realism; however it says much the same thing, allowing for both a critique of the Italian bourgeoisie, and a critique of the overtly realist approach taken to filmmaking before Antonioni and his contemporaries.

L’Avventura is dense in its complexity. It could be analyzed in many different ways, not only for its satire and storytelling, but also in formalist elements such as its unique approach to editing and narrative. Discussions of L’Avventura are usually focused on the liberated woman or the ambiguous ending. However, Antonioni’s ability to satirize Italian film while at the same time appealing to the Italian sentiment is a beautifully executed balancing act, which allows the film to straddle the fence between farcical and factual. L’Avventura tackles real social issues with the grace and subtlety that can only come with metaphorical storytelling, allowing generations of people to connect to and understand Antonioni’s works, rather than only appealing to his contemporaries.

Antonioni risked his budget and reputation to make films that addressed the multiple facets of humanity. Through the stories of love and loss he portrays, to the metaphors that represent the issues his home is divided by, Antonioni tells stories that anyone can find themselves in. His works are echoed today by films such as Get Out, The Truman Show, and Harold and Maude. These films, rather than tackling social issues head on, use genre, comedy and satire to embed them as subtext for a completely separate narrative. It is unique and creative storytelling that is rarely recognized for the artistry behind it. L’Avventura has come to represents an under-appreciated film movement that continues to influence film to this day.

Post-neorealism remains one of the longest running film movements in history; it continues today and will continue so long as there is a society to reflect upon.

*stills courtesy of Janus Films*

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.