- Starring

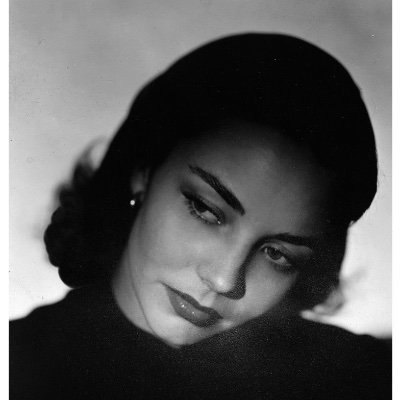

- Delphine Seyrig, Giorgio Albertazzi, Sacha Pitoëff

- Writer

- Alain Robbe-Grillet

- Director

- Alain Resnais

- Rating

- n/a

- Running Time

- 94 minutes

Overall Score

Rating Summary

Alain Resnais changed cinema forever with the release of 1959’s Hiroshima mon amour. It was sexy, poignant and visually ravishing; eventually Hollywood took notice. Of course, several films produced as part of the French New Wave, had an influence on New Hollywood productions and eventually bled over into mainstream blockbusters. Audiences were enchanted by the use of brief flashbacks, nonlinear narratives and languid pacing which amplified the dreamlike quality of the stories he tried to tell. Resnais’s follow up, Last Year at Marienbad, was released two years later and had a harder time earning international recognition versus the mainstream popularity of Hiroshima mon amour. This film is a far more challenging, inaccessible piece of work and it was easy to see why people were less seduced by its charms.

It is very, very hard to give anybody a general idea of what Last Year at Marienbad is about but let’s try anyway. X (Albertazzi), is at an opulent hotel in Marienbad and spends his time flirting with A (Seyrig). He is obsessed with her and believes that they met a year ago at the same hotel. In his mind, they formed a connection and could have potentially built up a romantic relationship. She contradicts his account of what happened and is certain that they never met. He also has to consider the fact that M (Pitoëff), seems to have significant sway over the decisions that she makes. All three characters circle around one another and try to figure out what they can get out of each other.

One can’t help but feel unsettled and pained throughout this film. It captures the feeling of grasping out and trying to reach something that can never be fully regained or understood. There is only the fuzzy memory of having felt the most ecstatic comfort and sense of stability. X felt as though he had known A his entire life, when they first met. They could converse with ease, played games together and could stand apart from the rest of the people staying at the hotel. At the same time, that serenity was not satisfying because it was fleeting and seemed to be slipping out of his grasp, even as he stood next to her. All of these ideas are underlined by a score that effectively captures the wistful yet angry tone that Resnais seems to be trying to capture. Most of the music employed by Francis Seyrig is performed on an organ and this ensures that we are immediately thrown off. This is the sort of music that would usually appear in a horror movie that involved allusions to Hell and Satanic rituals. It strikes the right note of mournfulness and depression. There is something audacious about how often the score is overlaid over footage of nooks and crannies within the palatial estate. Of course, music had been used this way before but it doesn’t just feel like the music is here to complement the images on screen in this film. Often it will prepare us for what we are about to see on screen or directly contradict the mood that the characters are trying to convey.

There is also something irresistibly French about the Chanel dresses Seyrig wears. Some might call that a superficial statement but it isn’t quite fair to object to the idea of beauty in cinema. Seyrig herself is naturally stunning but her little black dresses do a lot to accentuate her looks and remind us of how unattainable she is. In every scene, she looks like she has stepped out of a photoshoot for Vogue magazine. She alternates between being a cold, untouchable goddess and displaying brief flashes of warmth and charisma. This is what keeps us enthralled and we keep waiting to break through all of her protective layers and understand who she really is. We never truly penetrate her surface and are upset by the fact that she remains put together while X becomes increasingly bedraggled. We envy her and dislike her in equal measure. She is almost of her surroundings as she is always able to adjust herself to the new reality that X is always surprised by. She’s defined by her surface level appeal, so why not have her decked out in the most fashionable clothing you could find?

While Last Year at Marienbad may seem like it is operatic in nature and full of extravagant flourishes, that isn’t providing an accurate picture of what it actually feels like to watch it. X faces his own anxieties and fears about his relationship with this woman but we are able to watch on and look at his inner conflict as though we are anthropologists. The cinematography often suggests that we are viewing these people under a microscope. There is that famous shot of people standing on the walkway at the front of the hotel; the humans cast long shadows but the heavily trimmed trees do not. It creates an eerie effect and we begin to think of the humans as the only real thing in a constantly changing, surreal universe. We stop seeing them as flesh and blood people and think about them as a species of creatures. We study their behaviour and physical characteristics while considering how the inconsistencies in the world that they inhabit, cause them to lose their humanity. Shots like this are able to quietly throw us off balance. We think that we have finally pinned Resnais down and figured out what is happening but his vision eludes throughout.

In the end and being a first viewing, opinions could change over further viewings but for now, it feel as though it was hard to get the most out of it.

still courtesy of Rialto Pictures

Follow me on Twitter.

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.

I am passionate about screwball comedies from the 1930s and certain actresses from the Golden Age of Hollywood. I’ll aim to review new Netflix releases and write features, so expect a lot of romantic comedies and cult favourites.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.