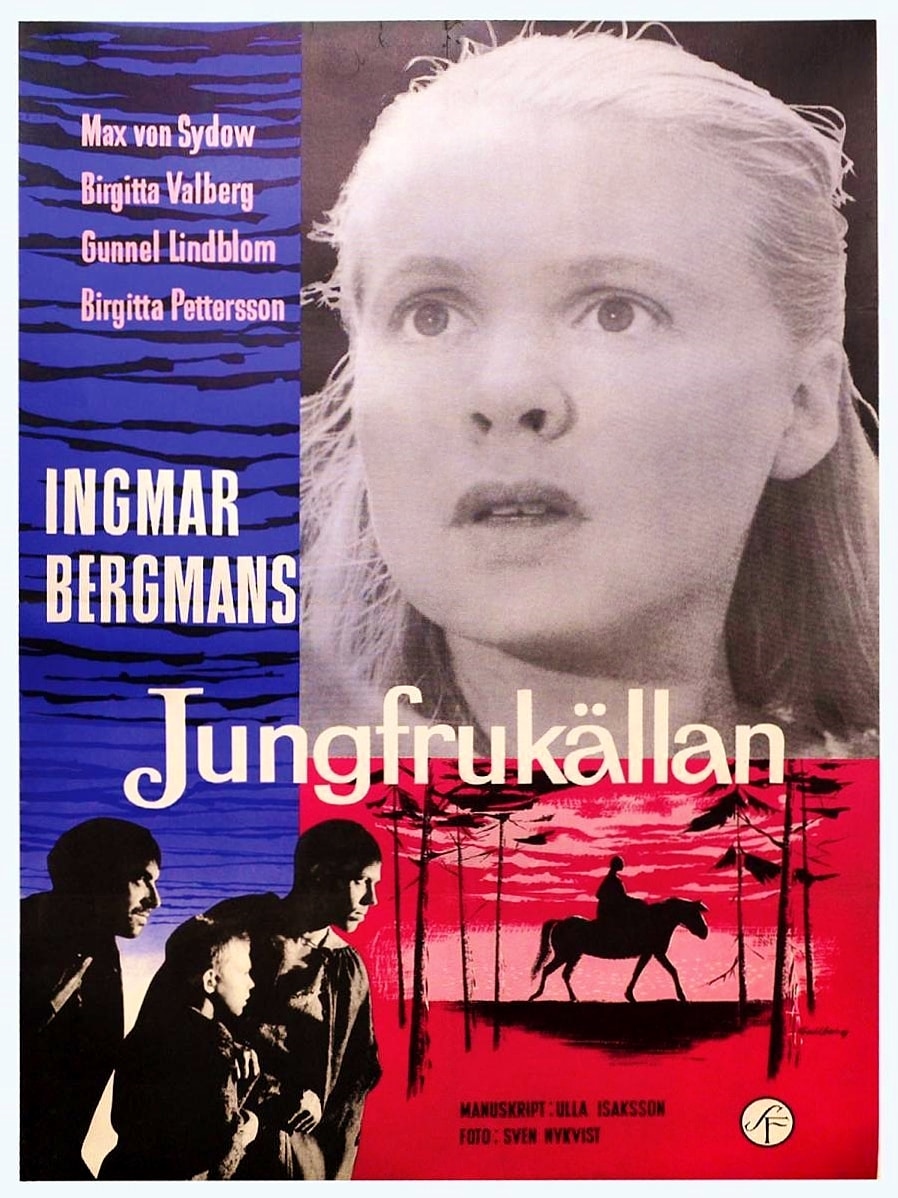

- Starring

- Max von Sydow, Birgitta Valberg, Gunnel Lindblom

- Writer

- Ulla Isaksson

- Director

- Ingmar Bergman

- Rating

- n/a

- Running Time

- 89 minutes

Overall Score

Rating Summary

Anybody who knows about Ingmar Bergman, probably knows that he was often preoccupied with examining religious guilt, the frustrating ‘silence’ of God and the difficulty of forgiving those who have wronged us. These are all very heavy, serious themes that are handled with the typical Bergman touch. At every turn, one feels as though they are being spoken down to by a paternalistic religious zealot who is convinced that he knows exactly what is right. The Virgin Spring is meant to be about characters who question whether it is ever acceptable to take revenge against people who have wronged you. This is a fine concept but when Bergman takes it on, he strips away most of the contemplation and seems to wallow in the misery and suffering, rather than standing back and displaying how painful it is to go through the grieving process. When the titular virgin spring appears, you might be unable to stop yourself from rolling your eyes.

The Virgin Spring is presented as a simple fable about religious guilt and redemption and features archetypical characters. It is set in medieval Sweden and focuses on a devoutly religious family who live their lives according to Christian principles. Patriarch Töre (von Sydow) is an arrogant, overly pious man who adores his virginal daughter Karin (Birgitta Pettersson). She is a mischievous young girl who enjoys wielding power over others and her servant Ingeri (Lindblom) resents the fact that she receives so much adoration from her parents. When Karin is sent by her father to take candles to the local church, he sends Ingeri to accompany and protect her on her journey. Karin stops to eat lunch and invites three herdsmen to join her in consuming her food. To her surprise, they proceed to rape and murder her. Ingeri watches from the shadows and does nothing to defend Karin. The herdsmen proceed to unwittingly put themselves in danger by staying at Töre’s house. He slowly realises that they have murdered his daughter and chooses to murder them in order to get revenge. This is a decision that he later regrets and he realises that he needs to learn how to demonstrate Christian love and forgiveness. He is able to receive this forgiveness when God spontaneously creates a spring in the place where Karin’s dead body had lain.

The Virgin Spring seems so dated and retrograde that it seems odd that Bergman would feel the need to tell it in 1960. It implies that non-Christian religions are an evil force, looks upon non-virginal women as worthless human beings who deserve to suffer and endorses an idea of ‘Christian forgiveness’ that seems morally suspect. One almost has to laugh at the fact that Ingeri, who is presented as a traditional ‘slut’, is also a non-Christian woman. We are meant to think that she is terrible because she got pregnant out of wedlock, didn’t have the good fortune to be born into a wealthy family and isn’t blonde and cherubic like Karin. It is made apparent that she could have been a good woman if she was a Christian and hadn’t been left pregnant, possibly as a result of being raped.

The depiction of her belief in Odin is so minimal that we aren’t given an opportunity to consider whether they should hold any weight. We just know that her beliefs are different and therefore not worthy of real consideration. It is troubling that Töre, a man who murdered several people, is presented as a good, decent Christian because the appearance of the spring allows him to regain his ‘innocence’ while Ingeri, the non-Christian, can’t go through the same automatic conversion. Why should innocence and blind faith be presented as a virtue? It is troubling that Töre feels that he can immediately let go of the guilt he feels, without appearing to fully examine why he feels this way and how he can change his ways.

Alternatively, one could interpret The Virgin Spring as a criticism of Christian values and the way that faith allows people to blind themselves to obvious truths. I want to see this as more than a simple endorsement of Christian values and excuse for Bergman to get all somber and depressed though it’s hard to see the film as something more complex. The acting is stiff, the symbolism is often groaningly obvious and the writing ensures that every idea is writ large. This is a historically important film because it united Bergman with longtime collaborator Sven Nykvist. That means that it is of some significance but one wonders why these talented men chose to tackle a story like this. Surely somebody offered them a better project during this period?

It’s hard for me to comprehend how anybody could read this script and want to make a film out of it.

still courtesy of Paramount Classics

Follow me on Twitter.

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.

I am passionate about screwball comedies from the 1930s and certain actresses from the Golden Age of Hollywood. I’ll aim to review new Netflix releases and write features, so expect a lot of romantic comedies and cult favourites.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.