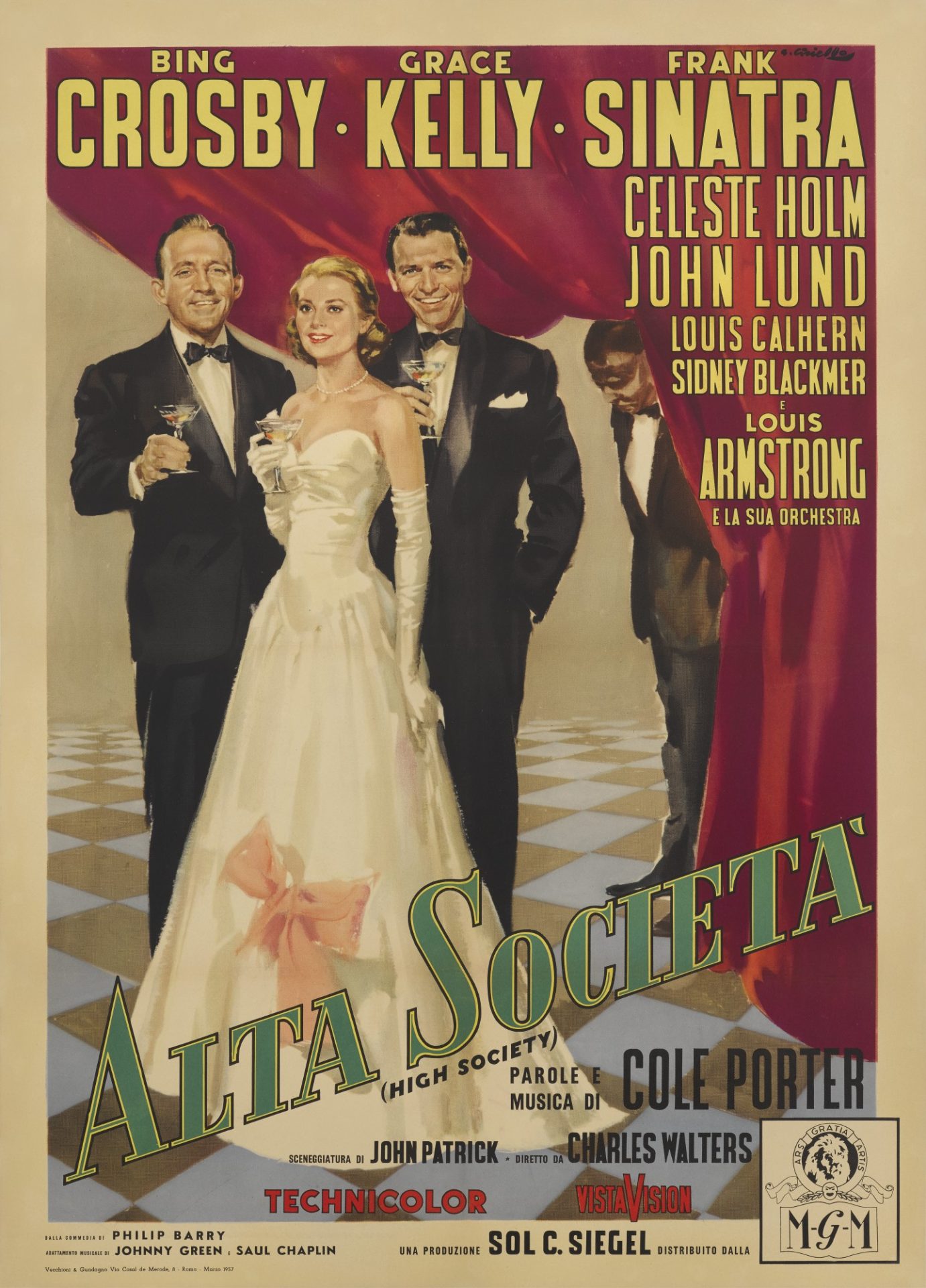

- Starring

- Bing Crosby, Grace Kelly, Frank Sinatra

- Writers

- John Patrick, Philip Barry

- Director

- Charles Walters

- Rating

- PG (Canada, United States)

- Running Time

- 111 minutes

Overall Score

Rating Summary

High Society is one of those remakes that so closely replicates scenes from the film that it is based on, that viewers sometimes question why they exist. When it seemed like the introduction of musical numbers would dramatically alter the tone and pacing of the film, screenwriter John Patrick appeared to be more than happy to copy and paste the dialogue from The Philadelphia Story. As somebody who doesn’t see the Katharine Hepburn classic as a flawless masterpiece, High Society should have tweaked some of the aspects of Phillip Barry’s play to make this story feel slightly more modern. Sure, the original features great performances from Hepburn and James Stewart, some witty dialogue and George Cukor’s typically elegant shot compositions, but its message is horrifying. If somebody had decided to excise all of the misogynistic, incestuous content from the script, nobody would have been complaining.

This iteration of the story brings back all of the same characters and situations. High Society is set in the world of rich socialites, as most Barry plays were, and centers on the romantic life of the infamous Tracy Lord (Kelly). She endured a brief marriage to C.K. Dexter Haven (Crosby), her childhood friend, and now prepares to marry the mild-mannered George Kittredge (John Lund). Haven still harbors feelings for his ex-wife and wishes that she would return his affections. Lord’s upcoming wedding plans are complicated by the fact that she and her mother are estranged from her philandering father, Seth (Sidney Blackmer), who regularly embarrasses the family by having affairs. In order to stop a gossip magazine from writing a story about her father’s affairs, the family has to agree to let reporter Mike Connor (Sinatra) cover the wedding. Connor quickly falls for Lord, and she finds herself caught between three different suitors. As she tries to choose which man she wants to marry, she also finds herself reassessing her relationship with her father.

The biggest problem that both films face is related to the presentation of Lord’s relationship with her father and ideas about what it means to be a good woman. Everybody is aware of the fact that times have changed and older films will feature outdated beliefs that you just have to tolerate and accept as a product of their time. High Society is different, in that it doesn’t just feature garden variety sexism. It features a scene that could have been ripped straight out of The Stepford Wives, in which her father states “What most wives don’t realize is that a husband’s philandering, even as innocuous as my own, has nothing whatsoever to do with me.” He says it in a snooty, high handed tone that implies that we all agree that rich, middle aged men should have the right to humiliate their wives and family members by sticking their penises into every young girl who is willing to give them a second glance. It is in this moment that the film fully reveals how sexist and classist it really is. When a wealthy older man has an affair, it’s socially acceptable, but one would think that Lord’s mother would be judged harshly by her husband if he found her having sex with one of the hedge clippers.

As that scene proceeds, things only get worse. Lord implies that his reason for having affairs is his fear of getting old. Then he claims that he needs, “The right kind of daughter. One who is full of warmth and affection. A kind of foolish, unquestioning, uncritical affection.” This statement is incredibly creepy on so many different levels. On one level, it’s gross that her father sees his daughter as serving the same function as the women who engage in illicit affairs with him. There is something disturbing about the fact that he equates these two types of women, and one can’t help but question whether he views his daughter in a sexual light. On another level, it is horrifying to watch a film that implies that the perfect woman is a doormat who will let a man do absolutely anything that his heart desires. Even if a man is making a decision that could put her life in jeopardy, it is her job to keep her mouth shut and gaze at him adoringly.

Throughout High Society, many characters tell Lord that she’s incapable of forgiveness and acts too much like a goddess to be a real ‘woman’. Presumably, all of the men in her life want the foolish, unquestioning, uncritical affection that her father described. The film doesn’t stop to consider whether Seth might be in the wrong, and certainly doesn’t expect him to do anything to regain the trust and respect of the women in his family. It is all up to Lord to make life easy for her father, and pretend that his mistreatment of her mother was of no importance. The stances that Barry takes on the role that women should play in society were sickening which made an otherwise fun musical, rather difficult to stomach.

That’s the biggest drawback when it comes to both films, and it was nice to see that High Society has most of the pleasures of the original. Kelly is as much of a fashion plate as ever, the Lord household is well appointed and the punchlines land more often than not. Celeste Holm excels in a supporting part that allows her to deliver every line in that wonderfully droll register that she put to use in many of her best roles. It even opens with a scene in which Louis Armstrong performs an entire song, before announcing “End of song, beginning of story”, if only all musicals could be as straightforward when it comes to transitioning between song and dance numbers and dialogue based scenes.

There’s also a certain fascination in watching a miscast Kelly tackling a role that doesn’t play to her strengths. On paper, she sort of does make sense for the role. She was born into a politically prominent Philadelphia family and her upper class background was incorporated into her screen persona. However, Lord was written for Hepburn. She’s fiery, independent, deeply insecure and concerned about appearing feminine. Hepburn and Kelly are different in that Kelly’s cool detachment and haughty attitude make her convincing as a devious, manipulative minx who might be able to manipulate the men around her. She possesses an unknowability that makes her more threatening than the highly emotional Hepburn, with her open face and ability to melt in the presence of her leading men. It’s strange to hear other characters criticizing her for being too tough or too demanding, when Kelly is never convincing as the type of woman who would attract that sort of criticism. In the opening scenes, it seems like she’s doing a watered down impression of Hepburn. She tries to imitate all of her unique affectations and that famous accent, yet nothing really clicks. Kelly possesses none of the unbridled passion that makes Hepburn’s volatility so compelling to watch.

As the film goes on, Kelly begins to capture viewers’ interest. She never becomes the version of Lord that the screenplay or other characters would have us believe she is, but Kelly puts her own spin on the role. She’s not a natural with comedy, so she seemingly decided to play this as a psychological thriller of sorts. Where Hepburn appeared to be negotiating with other characters and finding ways to tamp down aspects of her personality to please the people around her, Kelly seems to be having a full-on nervous breakdown. Her eyes will glaze over, her nostrils will flare and her entire body will seize up, when Lord is hit with the slightest provocation. It’s like she’s disassociating from her body and actively trying to block out everybody around her. If only she could have carried off the delivery of her one liners with more grace, but it’s hard to argue that she didn’t turn in an engaging performance.

It eventually becomes rather difficult to defend High Society. For every shot of Kelly in a pristine white bathing suit, one has to ignore the fact that the casting directors decided to hire Crosby to play a childhood friend of Kelly’s character. It’s immediately apparent that there is a 26-year age gap between the two of them and it’s hard not to burst out laughing when other characters talk about the fact that they grew up together. They should have just cut out references to them being childhood friends or cast an older or younger actor in one of the roles. It would have been such an easy adjustment to make, and one can’t help but wonder why somebody didn’t spend a couple of minutes cutting about five lines out of the script.

In the end, High Society isn’t quite as delightful as it should be. It mostly falls flat because of a few pesky flaws that could have easily been removed from the finished product. Still, with Kelly, Armstrong and dozens of Helen Rose gowns picking up the slack, it seems unfair to make too many complaints.

still courtesy of MGM

Follow me on Twitter.

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.

I am passionate about screwball comedies from the 1930s and certain actresses from the Golden Age of Hollywood. I’ll aim to review new Netflix releases and write features, so expect a lot of romantic comedies and cult favourites.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.