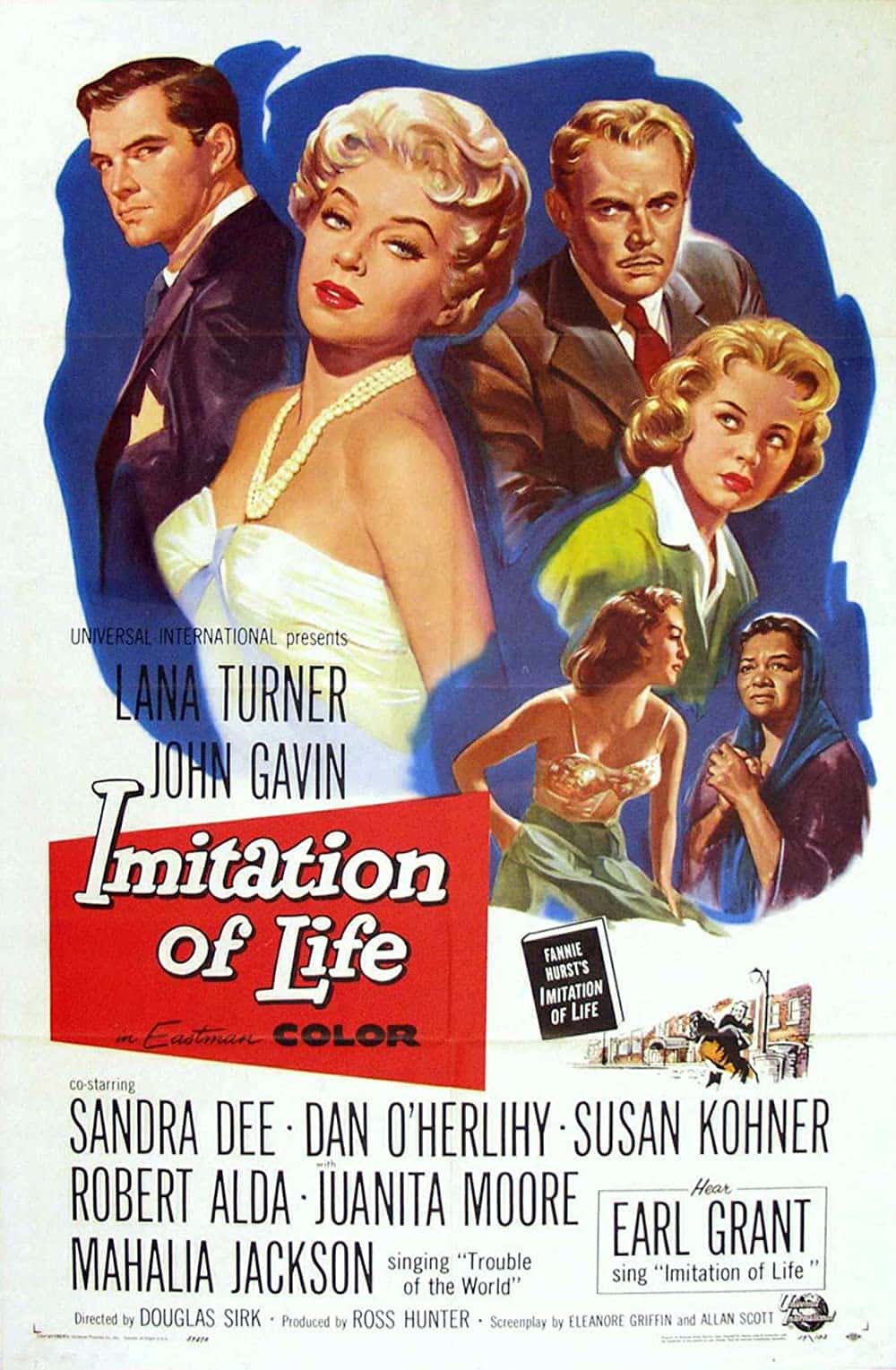

- Starring

- Lana Turner, John Gavin, Sandra Dee

- Writers

- Eleanore Griffin, Allan Scott

- Director

- Douglas Sirk

- Rating

- PG (Canada)

- Running Time

- 125 minutes

Overall Score

Rating Summary

Douglas Sirk’s 1959 adaptation of Imitation of Life is a remake of the 1934 film, directed by John M. Stahl. The story sees aspiring actress Lora Meredith (Turner) meets a homeless black woman named Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore) at Coney Island. After getting to know each other, Lora allows Annie to live with her in her apartment with their respective daughters, Susie (Dee) and Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner). The latter is light-skinned enough to pass as white, creating the central conflict of the film, as while she wants to be able to pass as white, Annie would rather live as black and not be ashamed of who she is. Meanwhile, Annie finds it difficult to balance her acting career with the needs of her own daughter.

Imitation of Life was Sirk’s last Hollywood movie before he returned to Germany, and it feels undeniably bittersweet that his success in America ended so abruptly. His melodramas were not appreciated at the time, dismissed as empty, vain women’s pictures, but today they are rightly appreciated for their striking usage of Technicolor, mise-en-scene, and prescient social commentary. He treated his socially trapped characters with compassion, and painted a scathing portrait of a commodified 1950s America, reflected in his garish, plasticky compositions that belied his critiques against American capitalism and everyone it threw under the bus.

If John Stahl’s directorial depiction of Lora showed how even the best intentions can be lost in conditioning to the society one is brought up in and the prejudices instilled within one’s self, Sirk is even colder and less forgiving of her flaws. As much as she can be kind to her friends and daughter, she seems to have little interest in their lives outside of how they benefit her. She seemingly cannot get past treating Annie and Sarah Jane like employees, and she is also capable of being cold, cruel and vindictive, such examples including her disregard for Annie’s fellow African-American friends, and when she forces Sarah Jane to serve dinner for her guests in direct retaliation against her behavior, weaponizing the very thing she’s most insecure about. Annie on the other hand, is conditioned to be subservient to her white friends and acquaintances, and cannot legitimately do anything about the power imbalance in her dynamic with Lora. While the original film could be interpreted as an earnest plea for something better in contrast with the dark implications of Jim Crow, this version shows how that better future seemed vastly unlikely, and it’s unfortunate how little has changed since then.

Sarah Jane, having seen what her mother has had to go through and not wanting to have to share in such suffering let alone have to be bullied for having a black parent, wants to live through the protection and privilege that passing for white with little concern for her mother. Like Stahl before him, Sirk does not ask us to take sides. Sarah Jane is perfectly capable of being cold and cruel, but Annie admits to her own selfishness in her desires for Sarah Jane, and is all too aware that being black in 1940s America means being deemed a second-class citizen. When we see Sarah Jane get brutally beaten by her boyfriend the instant he discovers her true ethnicity, it’s a stark reminder of how difficult passing really was back then.

Being a Douglas Sirk movie, the Technicolor of Imitation of Life is almost intoxicating. from Lora’s dresses, to the picture-perfect shades dominating the households, to the pastel overtones of Susie’s clothes, it’s the “ideal” America amped up to the nth degree. Punctuated with Frank Skinner and Henry Mancini’s pulsating, percussive, jazzy score, viewers get the sense of an oversaturated nightmare, an ostensibly perfect little world where everyone has to hide their feelings and issues. In reality, the world couldn’t be further from perfect, or even worthwhile for a lot of people. Moore and Kohner deserve the praise they’ve gotten as Annie and Sarah Jane, but Turner sinks herself into Lora’s meticulous calculations effectively, aided by good supporting work from Dee, John Gavin, Dan O’Herlihy, and Robert Alda.

In the end, Imitation of Life feels like a signifier to the closure of an era, where things were more uncertain than ever. This uncertainty pertained true to practically every facet of life, but especially that of the African-American experience pre-Civil Rights. The film observed what remained true over several decades through the 1940s and 1950s, and it still has the power to reveal what would stay true even after what was supposed to be a heyday.

still courtesy of Universal Pictures

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.