- Starring

- Ryô Yoshizawa, Ryûsei Yokohama, Soya Kurokawa

- Writer

- Satoko Okudera

- Director

- Sang-il Lee

- Rating

- 14A (Canada)

- Running Time

- 175 minutes

- Release Date

- February 6th, 2026 (limited)

- Release Date

- February 20th, 2026

Overall Score

Rating Summary

A decades-spanning melodrama in which the tragedies of art are matched by those in the lives of the performers bringing it to the stage, director Lee Sang-il’s sprawling yet composed Kokuho opens with text that sets the stage for the kabuki drama that consumes the lives of its subjects (and, by extension, the following three hours of your own); kabuki, since the days of its origins in 17th century Japan, has been a form of theatre traditionally occupied by men, regardless of the stated gender of the characters they play. In opening the film on this tidbit of context, one would assume that Kokuho has its sights set on gender-based or queer thematic subtext, but all that is cast to the side in favour of what’s right there on the surface.

Not to say that a film like Kokuho is in any way obligated to traverse these specific thematic grounds if they don’t fit the given path—not every film needs to be as layered in its discussion of gender and historical performance as Farewell My Concubine—but to bring them up and proceed to address them in only the most slanted of fashion is merely one of the myriad ways in which Lee’s ostensibly expansive saga of purpose and betrayal is unable to fully dig into its proposed scope beyond the general idea of an wide-reaching, epic piece of period tragedy. The years flash forward, but the performances onstage remain unchanging, and precious little dimension is found in those intervening moments when the curtain drops.

Despite its sprawling runtime and general inertia, the film wastes no time setting the heightened drama into motion the second those opening pieces of text fade into a view of the back of a kabuki performer’s neck painted ghost-white. That performer is Kikuo (Kurokawa; played as an adult by Yoshizawa), who puts on a dazzling show at a New Year’s celebration hosted by his father (Masatoshi Nagase); special guest and esteemed kabuki performer Hanai Hanjiro (Ken Watanabe) is certainly impressed beyond words at what he witnesses in the young boy’s talent. But only a few minutes go by before that celebration is raided by a rival yakuza gang and Kikuo’s father, himself a notorious gang leader, is shot dead right in front of his child.

Instantly taken in by Hanjiro and apprenticed as a burgeoning kabuki performer in his own right, Kikuo’s immediate taking to the craft puts him at odds with the master’s own son Shunsuke (Keitatsu Koshiyama; Yokohama as an adult). As the two boys grow together in age, talent and eventual esteem, only one of them can hold the mantle of the greatest kabuki performer in the world, and this quest for greatness will spark rivalries that ebb and flow with amicability and venom, all destined to endure a lifetime.

It is clear that this turbulent dynamic will cross decades, anyhow, because Lee will spend much of Kokuho jumping through the years as Kikuo and Shunsuke face peaks and valleys in their own journeys to the top; Hanjiro’s clear favouritism towards his new pupil puts him at a nurturing advantage where Shunsuke’s blood claim—kabuki is shown to be just as much about one’s family’s history in the art as one’s ability to perfect it themselves—gives him a more nature-oriented edge that aids him where direct encouragement doesn’t. Through it all, Lee’s juxtapositions prove intermittently swelling in their melodramatic heft, but more often find themselves stalling in the monotony of repetitive arc flows.

One pivotal scene, in which the spoils of one apparent betrayal lay the seeds for another, is stitched together with such expert command of the emotional sway it possesses that it’s astounding how Lee rarely, if ever, makes use of such forthright sentiment again. This counter-balance of hot and cold emotion—the precise repetition of kabuki taking centre-stage in both the film and these boys’ lives—would be far more engrossing if Lee and writer Sakoto Okudera prioritized the sting of that recurring sense of simmering betrayal under a more tacit, condensed edit, but the film’s endless droning is far too interested in letting these abridged performances play out than it is in exploring what they mean between the ellipses.

A film that is at once far too long and far too willing to cut between the moments that might inform those repressed sequences with a greater richness of character, Kokuho never soars to the passionate highs implied even in its most restrained bouts of rehearsed choreography—the film’s Oscar-nominated makeup and hairstyling does just as much to cake these boys in painstaking disguise as it does to put them at an emotional distance from each other and audiences. After more than half a century spent with these men as they flourish in the back-breaking art of kabuki, Lee Sang-il does little to give the impression that we’ve learned much more about them or their craft than we were told in that opening salvo of onscreen text.

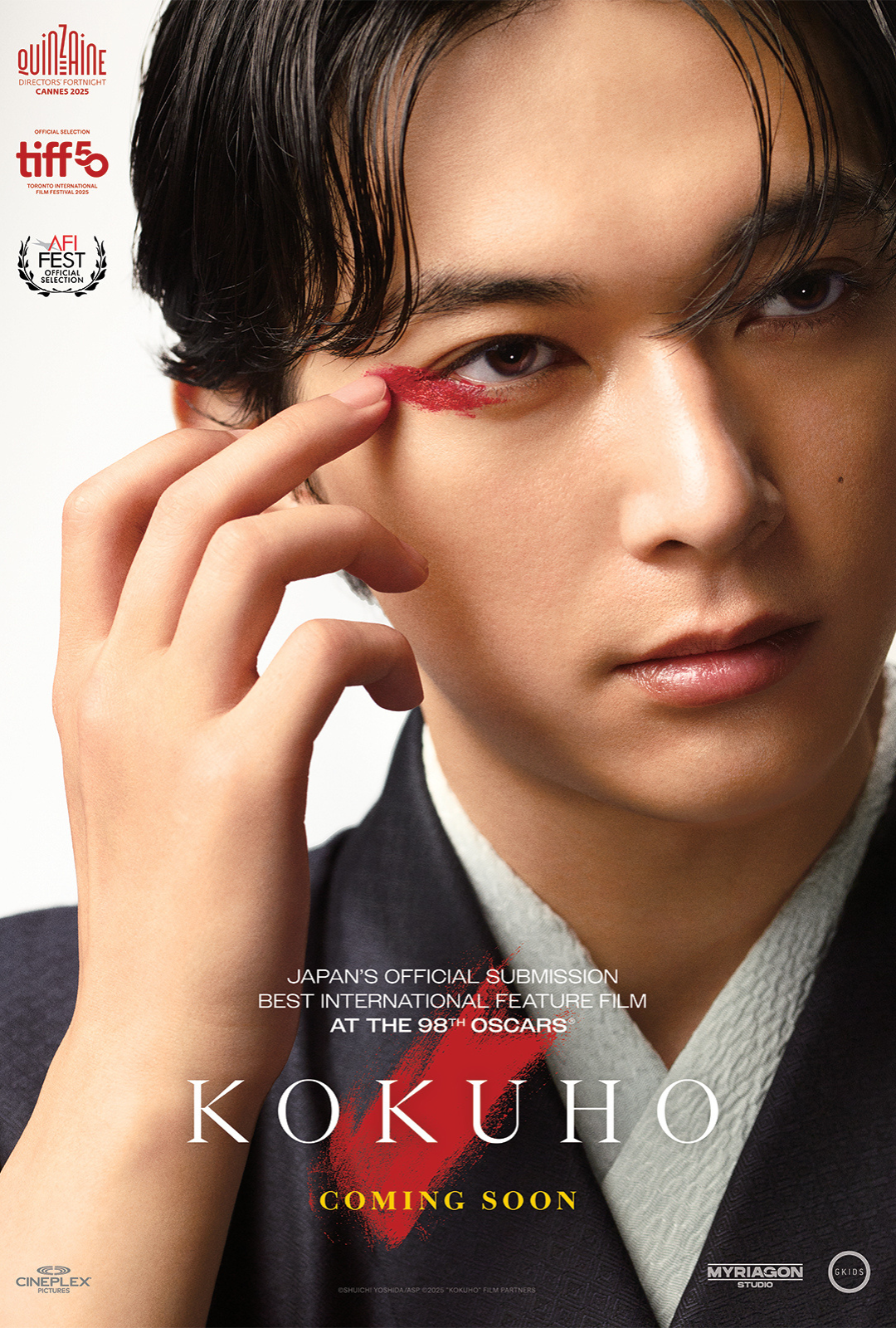

still courtesy of Cineplex Pictures/GKIDS

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.