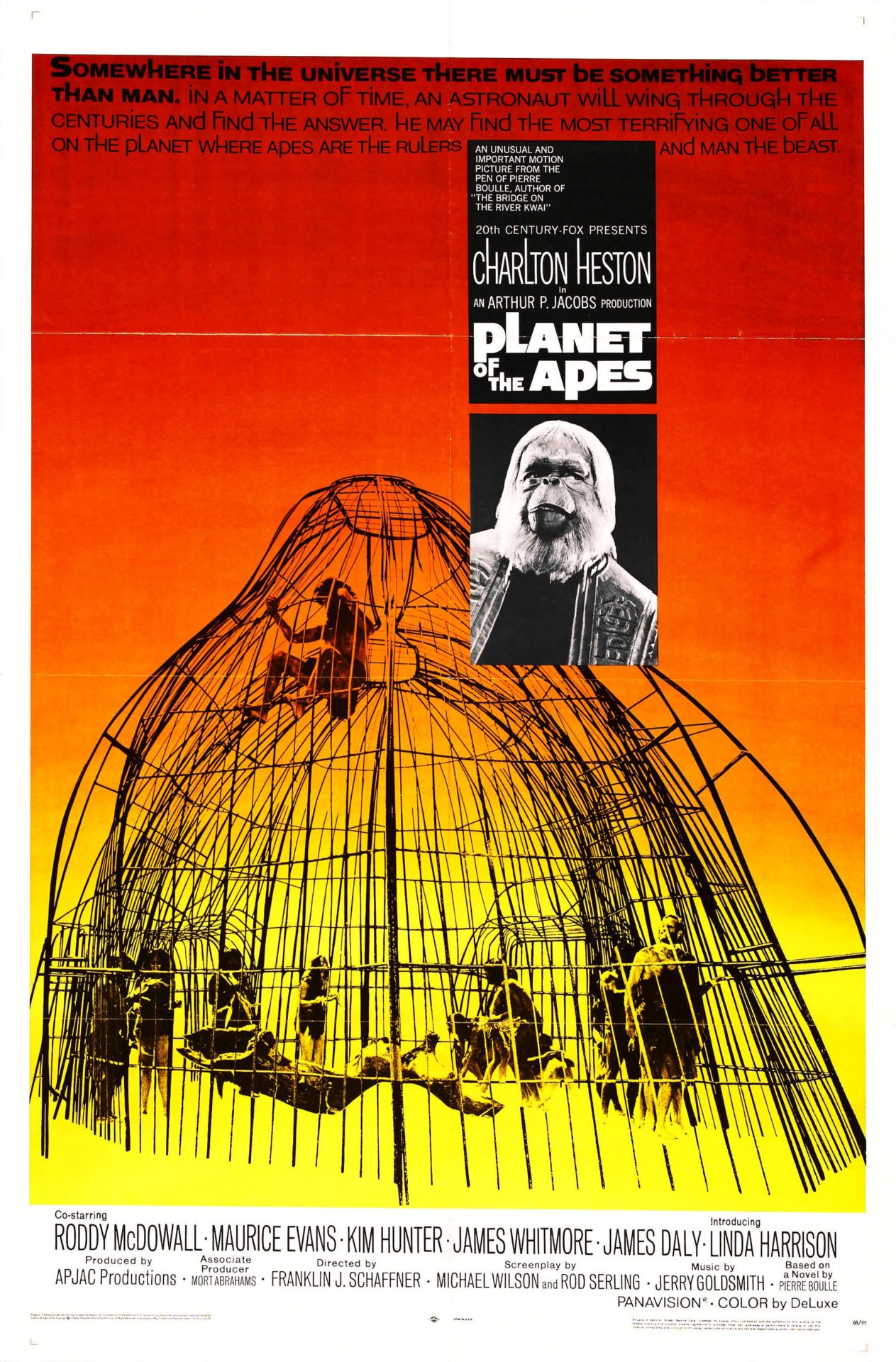

- Starring

- Charlton Heston, Roddy McDowall, Kim Hunter

- Writers

- Michael Wilson, Rod Serling

- Director

- Franklin J. Schaffner

- Rating

- G (Canada, United States)

- Running Time

- 112 minutes

Overall Score

Rating Summary

It seems difficult to imagine a time when science fiction was looked down on as a disreputable, frivolous genre by members of the critical establishment. In 2022, a significant portion of major film productions fit into the genre and major auteurs are generally expected to turn out a space opera or two after ascending to stardom. There are still plenty of junky Alien-rip offs that are briefly shown in theatres during the dump months but eggheads generally refrained from mocking Blade Runner 2049 and Ad Astra. This was not the case in the mid-1960s, when Robinson Crusoe on Mars could be greeted as one of the decade’s biggest critical punching bags. Things to Come and The War of the Worlds made some inroads with members of the general public but audiences were generally surprised when a new wave of sophisticated, intellectually challenging science fiction epics swept the screen.

2001: A Space Odyssey raked in $146 million dollars at the box office and permanently altered the conventions associated with the genre. It took a cerebral approach to considering the threats posed by humanity’s exploration of a new frontier and avoided making any obvious pronouncements about the many subjects that it tackled. Stanley Kubrick managed to confound cinema-goers and critics in equal measure and appeared to be several steps ahead of everyone else in Hollywood when he set out to elevate an art form.

The same could not be said of Franklin J. Schaffner, a journeyman director who turned out high-toned trash during the 1970s. He was assigned to direct an adaptation of Pierre Boulle’s satirical novel, La Planète des Singes, after J. Lee Thompson and Blake Edwards turned the project down. Producer Richard D. Zanuck had been attempting to get the project off the ground since 1963 and when things finally fell into place in 1967, the script had already been through several extensive rewrites. Zanuck envisioned Planet of the Apes as an ambitious showcase for pioneering prosthetic make-up and 20th Century Fox ended up pumping millions of dollars into the film’s arduous production.

The finished product bore a striking resemblance to the Biblical Epics that reached their apotheosis in the 1950s. Planet of the Apes follows George Taylor (Heston), a misanthropic astronaut who journeys across the galaxy during a light-speed voyage. He is accompanied by several other astronauts, who awake from hibernation when their spacecraft makes an unexpected crash landing on an unknown planet. Taylor is the only one of the astronauts to survive a grueling trek through the desert and comes across a settlement inhabited by anthropomorphized apes. He is imprisoned by local officials, who treat human beings like house pets, but receives sympathetic treatment from Zira (Hunter), an animal psychologist who is fascinated by his ability to verbally communicate. Taylor naively holds onto the belief that he can return to Earth and arrogantly assumes that he is superior to the local ape population. His ideals are ultimately challenged when the apes allow him to run free and he is confronted with shocking revelations about the history of the mysterious planet.

Screenwriter Bill Lancaster made the choice to de-emphasize the satirical nature of the novel in order to make way for a more conventional melodramatic storyline that pits a virile man against a community that ignores his protestations of innocence. He even includes dozens of scenes in which Heston is given the opportunity to bloviate about the conflict between free will and determinism. The second half of the film is virtually indistinguishable from the gobbledygook that Cecil B. DeMille was fond of producing. If you removed Hunter’s ape prosthetics and draped her in a cloth tunic, you could easily convince yourself that this was a sequel to Quo Vadis. Everything moves at a slow, deliberate pace and every theme is highlighted and underlined in a vaguely insulting manner. Lancaster is so concerned with getting the audience to take his lethargically paced courtroom drama seriously that he forgets to take advantage of the story’s relatively unique setting.

It’s fair to say that Planet of the Apes is at its most electrifying when it presents its hero as a stuck-up press who cannot reconcile his antisocial tendencies with the superiority complex that he suffers from. His comical befuddlement is effectively illustrated during the film’s opening, in which he is forced to trudge through a foreign environment that also happens to be eerily familiar. The film dips into the uncanny valley during this brief period of time, so it’s deeply disappointing when Taylor gets locked up and Rod Serling’s social commentary starts to get a whole lot clumsier.

The ending, which was presumably intended to be bleak and darkly funny, is stymied by Heston’s ego. In an ideal world, the whole film would play as one long sick joke that asks us to titter at the sight of this warmongering chauvinist strutting around in a loincloth. Unfortunately, Serling’s critiques of religious bigotry and historical revisionism are so broad that the ending lands with a thud. His attacks are so heavy handed that they don’t discomfit the audience or force them to examine their own prejudices.

Planet of the Apes is much schlockier than the other innovative science fiction films that propelled the genre into the mainstream and, as a result, it ends up seeming far more dated than many of its contemporaries. One can tell that there’s a decent concept buried under all those animal skins but Schaffner works hard to conceal that fact. One is also forced to consider whether producers took the wrong lessons from the success of this film and determined that empty spectacle was more significant than anything else when it comes to drawing teenagers into theatres.

In the end, perhaps the history of cinema would be littered with less mass-produced trash if Planet of the Apes had never been made.

still courtesy of 20th Century Studios

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.

I am passionate about screwball comedies from the 1930s and certain actresses from the Golden Age of Hollywood. I’ll aim to review new Netflix releases and write features, so expect a lot of romantic comedies and cult favourites.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.