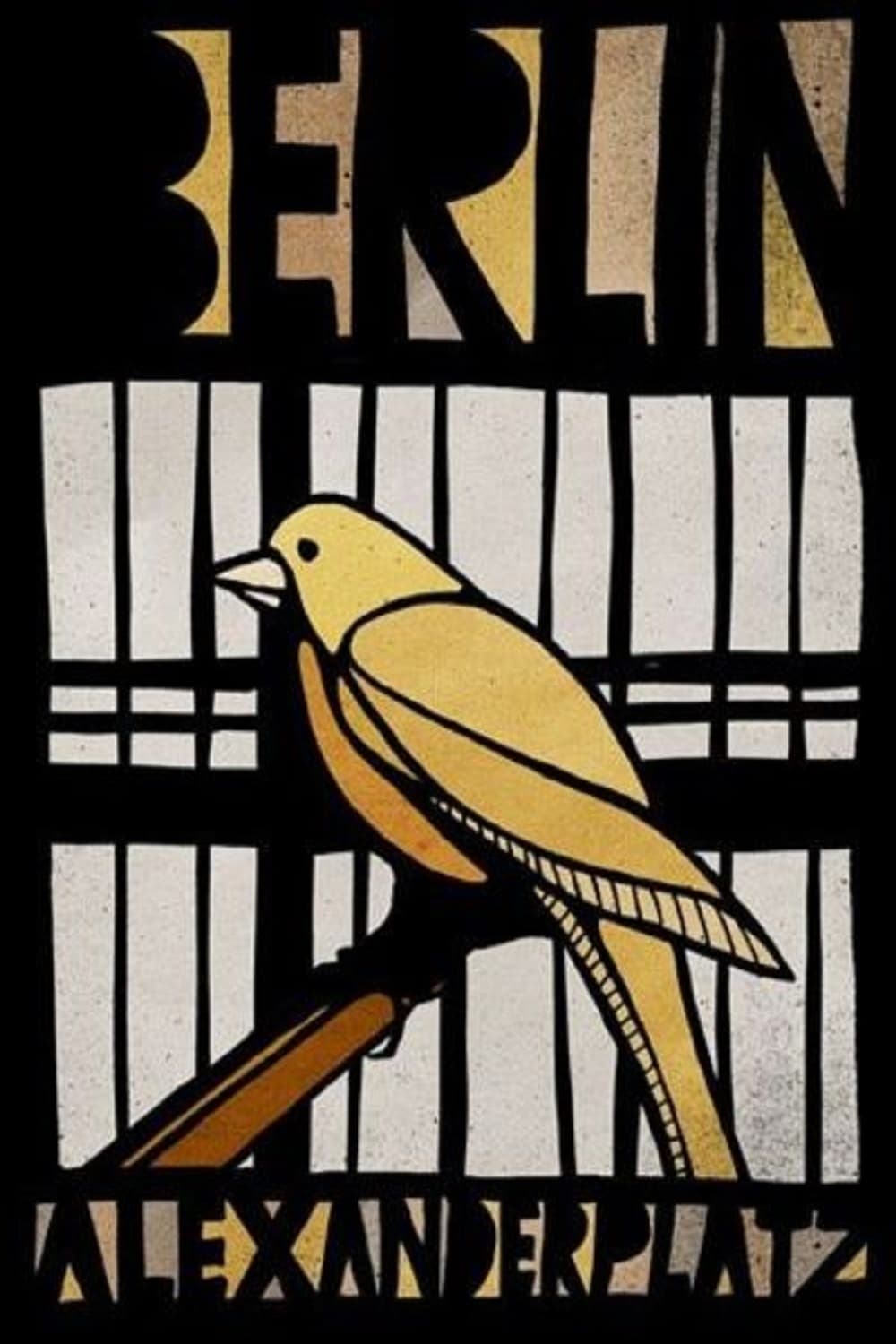

- Starring

- Günter Lamprecht, Claus Holm, Hanna Schygulla

- Writer

- Rainer Werner Fassbinder

- Director

- Rainer Werner Fassbinder

- Rating

- n/a

- Running Time

- 931 minutes

Overall Score

Rating Summary

Berlin Alexanderplatz is a miniseries about self pitying, proudly ignorant people who refuse to take accountability for their actions. Most stories are about flawed figures who find ways to grow and develop into better people. They learn lessons and surround themselves with kind, caring people who only want the best for them. It draws its power from the fact that it doesn’t follow a traditional arc. It is content to stew in the horrific criminal underworld of Berlin in the 1920s and there is never a moment at which it reassures that everything will work out just fine. The inertia becomes the point and viewers are left to accept the fact that stagnation can have a devastating impact on any individual.

It is fitting that Rainer Werner Fassbinder took on the challenge of writing and directing such an ambitious project. He was fascinated by self involved individuals who busied themselves with complaining about the cards they had been dealt, rather than confronting the realities that they were faced with. There’s a little bit of Petra von Kant and Emmi Kurowski in Franz Biberkopf. All three are predatory, grotesque figures who prey on the vulnerabilities of others. They do this whilst viewing themselves as downtrodden, weak victims who have been oppressed by society. They never quite come to terms with their own hypocrisy and their efforts at self examination are drowned out by their self pity. Biberkopf is easily the most vicious and violent of the three as Fassbinder never seemed to expect anyone to sympathise with him. This is one aspect of the series that is difficult to deal with, as the majority of the characters are murderers, rapists, anti-Semites or onlookers who tacitly encourage their damaging behaviour. One needs to get past their disgust in order to form a deeper understanding of what drives these people.

Berlin Alexanderplatz sees Biberkopf (Lamprecht) is introduced as a hardened criminal who is being released from prison after serving a four year sentence for having murdered his wife Ida (Barbara Valentin). He claims that he wants to change his ways but quickly returns to his old lifestyle when he fails to financially support himself through legal means. He enters into a co-dependent relationship with Reinhold (Gottfried John), who has Biberkopf seduce his girlfriends when he wants to break up with them. Reinhold feels a great deal of guilt for his actions and Biberkopf comes to believe that he can advise him on how to live life as a good and moral man. Their relationship is abusive and it feeds into both of their toxic impulses. When Biberkopf falls for Mieze (Barbara Sukowa), a childlike prostitute, she also catches Reinhold’s eye. She finds herself trapped between two predatory men and is helpless to stop both of them from abusing her. Reinhold ends up making a decision that permanently alters Biberkopf’s worldview.

On its face, this is not an exceptionally original or exciting story. The tale of the immoral criminal, trying to go straight before being drawn back to his old ways, with disastrous consequences, has always been a staple of the crime genre. Berlin Alexanderplatz is special because it uses those formulaic plot beats to make points about the decay of a society that is barely functioning as it is. Because Fassbinder takes such a long time to tell this story, the audience gets a better sense of the passage of time and can really get to know this cast of characters. In a feature film, Reinhold might have felt like a two dimensional villain who shows up to disrupt the peace in the third act. There wouldn’t have been enough time to explore the complexities of his relationship with religion and his intolerable hypocrisy. Stock characters and tropes are fleshed out and given little idiosyncrasies that make them feel unique to the world that Fassbinder establishes.

Everything to Berlin Alexanderplatz is drab and grey or macabre and sweat soaked. Fassbinder is happy to film incredibly long, drawn out scenes in which multiple characters converse, in one location. The tension slowly builds and the walls seem to be literally closing in on the characters. They never leave the cramped, poorly insulated apartments that they inhabit and their problems seem to be eating them alive. The slow pacing gives these talks a feeling of naturalism that is sorely needed. These scenes are often more about Biberkopf’s inability to communicate with the people around him, and less about the content of their discussions. The script is full of moments in which Biberkopf will get diverted and start delivering lyrical poetry that seems to be more literary than it is cinematic. This only adds to the feeling that he is isolated from the people around him and can’t shake off his own prejudices in order to properly digest what they are saying to him. It also allows this series to retain its literary roots and it means that there are times when Biberkopf can tell the audience exactly how he feels. That’s supposed to be a cardinal sin in the world of screenwriting but Lamprecht and the rest of the ensemble deliver all of this unusual dialogue as though it comes naturally to them.

There is so much to take in that it feels impossible to truly do it justice. It’s hard not to tear up at the beauty of Fassbinder’s beloved pink lighting or his magnificent use of trees as metaphorical representatives of Reinhold’s moral decay. It was all so superlative that those little details held it back from being considered a masterpiece. Meanwhile, the score felt a little too dated for something that was so cutting edge in so many other ways. It was always jarring when a shamelessly sentimental harmonica tune would start playing over scenes in which something mildly positive happened. Any subtlety went out the window, leaving a misshapen melange of George Jones during his Tammy Wynette period and the harsh realism of New German Cinema. There was also the fact that Mieze was a character who inspired little interest. It is clear that she will meet a tragic end as soon as she appears on screen and it becomes very difficult to care when the inevitable outcome is so glaringly obvious. To some degree, it had to be this way, but one wonders what might have been if she had been more of an engaging presence in this bleak, miserable tale.

Despite reservations, this stands as a monumental achievement on Fassbinder’s part. it’s tough to think that there will be anything quite like it.

still courtesy of The Criterion Collection

Follow me on Twitter.

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.

I am passionate about screwball comedies from the 1930s and certain actresses from the Golden Age of Hollywood. I’ll aim to review new Netflix releases and write features, so expect a lot of romantic comedies and cult favourites.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.