- Starring

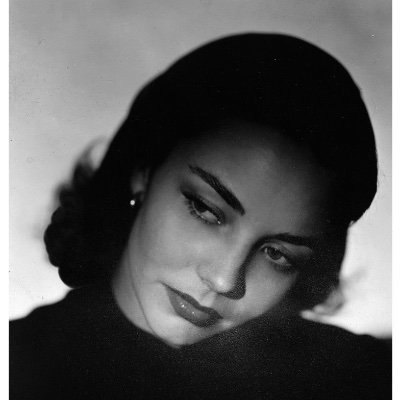

- Anna Karina, Margit Carstensen, Brigitte Mira

- Writer

- Rainer Werner Fassbinder

- Director

- Rainer Werner Fassbinder

- Rating

- n/a

- Running Time

- 86 minutes

Overall Score

Rating Summary

Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s cinema can seem forbiddingly intellectual and unusually cold. His characters often seem distant from the people around them and, by extension, distanced from the audience. So often, we crave the experience of relating to characters and feeling as though a film has allowed us to walk a mile in their shoes. It’s only natural to want to consider how you would fare in the situations they have been placed in, and films famously serve as machines to create empathy. Fassbinder did understand that impulse and The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant does feature a fragile, achingly human protagonist who shatters in front of our eyes. She was a raw nerve who couldn’t help but open herself up to anybody who was willing to watch her. He seems to have made a conscious decision to alienate the audience from the characters in Chinese Roulette. This time, the lion’s share of attention is meant to go to the director himself.

With Chinese Roulette, he returns to telling a tale about essentially immoral people who are eventually punished for their actions. Centrally, the film is concerned with the marriage of Ariane (Carstensen) and Gerhard (Alexander Allerson). They are both middle class and appear to have a relatively happy relationship. They also work together to raise their physically disabled daughter Angela (Andrea Schober) who has grown spoiled as a result of coddling. This illusion begins to shatter when they each go away for their weekend with their respective lovers. Ariane is involved with Kolbe (Ulli Lomell), who happens to be Gerhard’s assistant, and Gerhard has had a long-term ‘arrangement’ with the elegant Irene (Anna Karina). When all four lovers become aware of one another, they find it increasingly difficult to remain civil.

One is almost always conscious of the guiding hand of the director when you watch a film, but it is rare to feel like the director wants to take precedence over the content presented on screen. Fassbinder really wants the audience to be aware of the fact that this whole story is being filtered through his perspective and he is picking and choosing which aspects of the story he wants to tell. Our awareness of his guiding hand creates a lot of discomfort when we notice how he often neglects to include Cartis’s reaction shots in several scenes. It feels as though he is cutting her out of the narrative in order to remind us of the traditional standards of morality that might have governed a story like this, if it had been told by a Puritan in the 18th century. We begin to see this as a criticism of morality tales, that asks us to reconsider how we view the ‘Other Woman’ or the disturbed child from a broken home.

Chinese Roulette also sees Fassbinder slightly adjust some of the traits that stock archetypes would have, and this has the effect of startling us. At first, Angela seems like the sort of evil child that would go on to regularly populate Michael Haneke’s series of dramas about the degradation of society. She has suspiciously rounded cheeks, glassy eyes and a reedy voice. This can only mean that she’s up to no good and represents all of the horrors that younger generations have inflicted upon society. Fassbinder surprises us by presenting Angela as a girl who doesn’t derive sadistic pleasure out of tormenting others. He also doesn’t push her too far in the other direction, by turning her into some sort of heartless ice queen who is incapable of feeling compassion or empathy. She is an ordinary little girl in many ways, governed by embarrassment over her infatuation with Gabriel (Volker Spengler) and often confused by the way that her parents communicate.

She seemed to be somebody who desperately wanted to be a sociopath, and her empathy and compassion were holding her back from being the cold, emotionless manipulator that she wanted to be. This makes her fairly detestable, as she is fully aware of how much pain she is causing, but it also puts us in an uncomfortable position when it comes to judging her, or any of the other characters. We can’t dismiss all of them as bourgeoise pigs who deserve to suffer for their hypocrisy and unfeeling attitudes towards others. They all possess some degree of self awareness and edge closer and closer to making discoveries about themselves. There is the possibility that they could all become decent human beings if they just got their priorities in order. That is what makes it so tragic when their intellectual mind games lead to violence.

Perhaps Fassbinder was trying to argue that all efforts at self improvement and genuine honesty can be overridden by humanity’s desire to solve problems with brute force. There are aspects of human nature that are essentially weak and self sabotaging. We want criticisms to be softened in order to properly accept them and are in constant need of effusive praise. It is painful when the people around us vocalise the concerns that we have always had about ourselves. Chinese Roulette points out that we can’t simply become sociopaths and turn away from the pains of the human condition. These characters are relatable in their own way, although it takes a considerable amount of time to embrace them. Their prickliness and objectionable behaviour turns us off, and that makes this a very difficult viewing experience.

Chinese Roulette may not be easy to sit through, but it will leave viewers with a lot to ponder. This is one of those films that is most satisfying when seen with a group. This creates the opportunity to mull over it after seeing it and it might make it easier to come to terms with some of the more challenging material. There is enough here to justify a three-hour, navel gazing conversation. It may sound pretentious, but sometimes one has to risk seeming like they’re up your own arse when it comes to arthouse cinema.

Follow me on Twitter.

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.

I am passionate about screwball comedies from the 1930s and certain actresses from the Golden Age of Hollywood. I’ll aim to review new Netflix releases and write features, so expect a lot of romantic comedies and cult favourites.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.