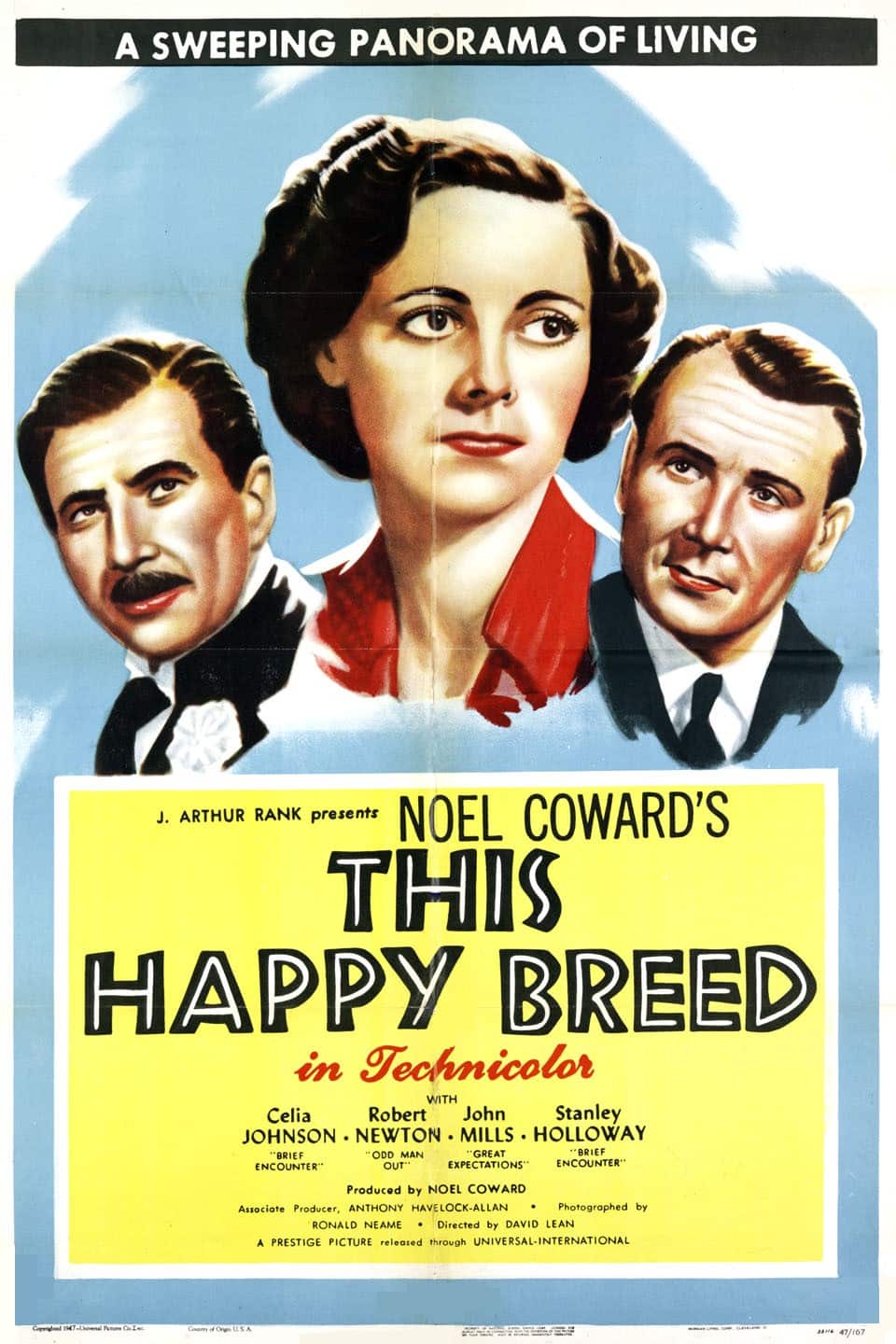

- Starring

- Robert Newton, Celia Johnson, Amy Veness

- Writers

- David Lean, Ronald Neame, Anthony Havelock-Allan

- Director

- David Lean

- Rating

- n/a

- Running Time

- 115 minutes

Overall Score

Rating Summary

Those familiar with the work of Noel Coward can definitely see a lot of throughlines; intergenerational conflicts, messy people weaving through how to make a complicated relationship work, melancholic longing while knowing that it might not work out as desired, acerbic, sophisticated humor, a healthy dose of British patriotism, and historical backdrops giving them a sense of dramatic weight. The closest comparison to This Happy Breed would be Cavalcade in that they both fall under the Coward template of the chronicling of an intergenerational family affected by historical events. This film is more affecting because of the emphasis on the individual characters rather than how important the historic backdrops are. Unlike the latter, the family at the center here actually face consequences, losses, and are required to navigate their way through the commotion of the real-life World Wars that devastated so many lives.

This Happy Breed tells the story of an inter-war suburban London family the Gibbons – Frank (Newton), his wife Ethel (Johnson), their three children Reg (John Blythe), Vi (Eileen Erskine) and Queenie (Kay Walsh), his widowed sister Sylvia (Alison Leggatt) and Ethel’s mother (Veness) – against the backdrop of what were then relatively recent news events, moving from the postwar era of the 1920s to the gradual inevitability of another war, and social changes such as the coming of household radio and talking pictures in the cinema. Frank is thrilled that their next-door neighbor is Bob Mitchell (Stanley Holloway), a friend of his from his first days in the army.

The film’s usage of the World Wars as part of its storytelling was a highlight as it showed how the differing beliefs it spurred affect the Gibbons family. It’s not that any of them believe any obviously wrong ideals, but that they have differing ideas on things like privilege and familial responsibility. And like any ordinary group of people, they also want to engage in whatever enjoyable escapism they can, whether it be Sam and Vi watching a new talking picture at the cinema in 1929, Queenie winning a Charleston dance contest the year prior, these can be vivid moments in one’s young adulthood, especially when facing the hardship of the real world.

With This Happy Breed, Coward, director David Lean, and co-writers Ronald Neame and Anthony Havelock-Allan understood the little and big moments that define any believable family. The Gibbons love each other, but they are differing personalities that clash when tensions are high. Like with all families, they bond, fight, fall out, hurt, and at the best of times, reconcile even when it seems impossible. There is a lot said about how there are certain things that both the parents and the children don’t quite understand about each other, what they do understand about each other, and how their parent-child relationship grows with time. Also believable are the sibling relationships; siblings will often fight no matter how close they are. They are transitioning into young adults and undertaking the emotional process and growth that comes with such. They will also have different perspectives on similar things, and/or have completely different interests. The best sibling relationships come from being able to value the moments of bonding over experiences or shared interests, and being willing to work with each other when it is required.

The dinner table argument between Queenie and socialist friend Sam Leadbitter (Guy Verney) is a great example of the film’s focus on ideological and philosophical debate, with the latter grandstanding over the former’s privileged stances, particularly her desire to leave her home for ‘bigger, better’ opportunities, and her complacency and being content with the all-consuming, destructive capitalist system that widens the gap between the rich and the poor that they exploit. Sam even makes a point to off-handedly jab at Queenie’s appetite (“You leave my stomach out of it,” she snaps back).

This Happy Breed, moreso than a film like Mrs. Miniver, understands the nuances and complexities that come with movements like the Nazi Party and the British Union of Fascists. They were obviously terrible, hateful ideologies for which there should be no tolerance under any circumstance, but the movie treats these movements as being run by ordinary people rather than superhuman machines, and how these movements can affect literally anyone, not even in the sense of simply converting innocent bystanders, but in the many ways that people react to it. The film was also not afraid to call out some of the hypocrisy in which British politicians like Neville Chamberlain responded to rising fascism, how people like him were content to bury their heads in the sand instead of facing the truth at hand, to say nothing of the blindly enthusiastic applause that it would’ve emitted.

The cinematography by Ronald Neame is a great asset; unlike most movies from this era, Neame utilizes Technicolor for the sake of realism rather than escapism. Nothing here looks garish, but rather natural, from the complexions to the clothing. What stood out the most was the nutty browns and the minty greens of the Gibbons household, and as usual, the crisp breath-catching coldness and glowing sunsets of the winter mornings, to the general harshness yet somehow blissful idyllic promise of winter in general. The usage of color to depict the wars was particularly effective and devastating, with the blazing reds standing out.

The acting is uniformly excellent. Walsh was the personal standout for her defiant, idealistic Queenie. Her fallout and reconciliation with her mother is heartbreaking and affirming, and in many ways she represents the very heart and soul of this movie, reflecting each of our own desires to achieve an exciting, fulfilling life. Johnson imbues a worn, weary sense of history and anxiety into Ethel, who has to support her family and deal with when some of them let her down. Especially because of Johnson, Ethel represents what a struggle it must’ve been being a housewife in the 1940s, struggling to keep up with societal expectations, while finding some sense of enjoyment in the downtimes. When she disowns Queenie, viewers are left deeply upset. Robert Newton is properly rugged yet equally worn-out as patriarch Frank, who tries to do his best for his family yet can’t always meet their collective expectations. He also shows the struggle of being a war veteran; the guilt, the pain and the stress. Elsewhere, Holloway, Veness, Erskine, Blythe, Verney, and John Mills are all varying levels of excellent in their respective parts. Holloway’s character Bob in particular is well-utilized to represent more ideological and philosophical differences, particularly putting too much stock into the League of Nations.

This Happy Breed meditates on the struggles of a family during a crisis while offering a compelling perspective on humanism and complexity. David Lean and Noel Coward’s perspective on humanity and familial complexity work perfectly.

still courtesy of Criterion

Follow me on Twitter, Instagram, and Letterboxd.

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.