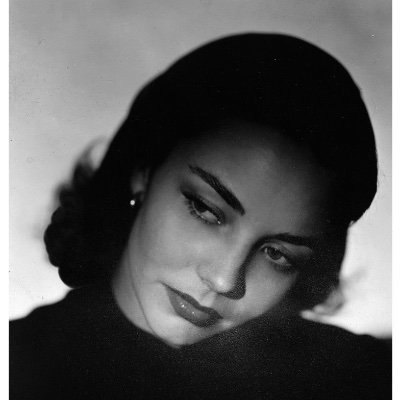

- Starring

- Maurice Ronet, Léna Skerla, Yvonne Clech

- Writer

- Pierre Drieu La Rochelle

- Director

- Louis Malle

- Rating

- n/a

- Running Time

- 108 minutes

Overall Score

Rating Summary

Louis Malle’s The Fire Within might just be the ultimate serious, slightly pretentious French art film. Its poster features an anguished looking man staring off into the distance with a giant, mysterious red X painted across his face. Naturally, its plot hinges on the idea that it’s better to be dead than to be bourgeois. There may be no sentiment that better embodies the viewpoint of snooty Frenchmen. If that isn’t enough, it also features black and white cinematography and a limited use of dialogue. All of this initially made it seem rather off-putting. One can only take so much of wealthy French artists complaining about middle class non-artists who apparently don’t deserve to live comfortable lives and should feel guilty for wanting to own a home and have a family. Fortunately the film is more than just a screed against middle class family men. It never develops into a film of great depth, but it does does provide Malle with an opportunity to play around with many of the assets that would make appearances in his later work.

Rather than being a semi-autobiographical work, The Fire Within is based on a novel by Will O’ the Wisp which covers some of the same ground. The protagonist, Alain Leroy (Ronet), is a war veteran who became a lively bon vivant in the years following his service. His life began to go downhill when he became an alcoholic and found that it was impossible to maintain a real romantic relationship with a woman. Leroy was so burnt out that he entered into a rehabilitation clinic and tried to overcome his addiction. After going through treatment, he enters back out into the normal world and begins to ponder committing suicide. He decides to walk around Paris for a day and try to reconnect with his old friends, in an effort to raise his spirits. When Leroy realizes that all of his friends have entered into the middle class, he becomes incredibly depressed.

This reviewer found themselves getting rather irritated as yet another French intellectual who was born into wealth, took his opportunity to rail against other rich people. Maybe the notion that artists are somehow more special than doctors or lawyers or businessmen and don’t do their jobs for the money was an annoying one. If they were truly selfless and only concerned with producing beautiful artworks that would change the world, they wouldn’t command such high salaries. Malle apparently owned a palatial home in Beverly Hills, dined at the best restaurants in Paris and walked around in fairly expensive clothing. He chased status symbols and financial stability as much as anybody who wasn’t working in the entertainment industry. This is one of the reasons why it’s easy to take issue with the disdainful view that artists take of the middle class. If they acknowledged that they were part of the problem, one might be more willing to accept the feeble arguments that they make. Because they look down on non-artists and act as though they are above material concerns, their screechy protestations against the middle class seem hypocritical.

Even though it’s easy to take issue with some of the ideological arguments within The Fire Within, Malle’s efforts to tell a story through visuals was still admirable. Suzanne Baron’s editing aids his efforts to highlight Leroy’s feelings of discomfort and total lack of agency. She employs the sort of invisible editing that had fallen out of favor in the early 1960s and gives the film the energy of a Classic Hollywood melodrama. There will be wide shots of Leroy puttering around his room and wondering whether he will ever be able to achieve satisfaction without having alcohol in his life. Baron finds subtle ways to cut between shots of him in different parts of the room and doesn’t use flashy jump cuts to draw attention to her own work. She finds ways to make the audience feel the duration of the long hours that Leroy spends in his room. When Leroy is out on the street, she cleverly keeps us on the hook and we find ourselves waiting for Leroy to fall off the wagon and begin drinking again. Baron drums up tension without including repetitive shots of glasses of alcohol, which tempt Leroy from afar. She brings so much to a film that might have seemed slight without her efforts.

In the end, The Fire Within was not a high point in Malle’s long and illustrious career. Despite the fact that it pales in comparison to Atlantic City, the film is still essential viewing for those looking to understand his career as a whole. Some consider it to be one of his finest early works and it is easy to see why it garnered so much international attention back in 1963.

still courtesy of Governor Films

Follow me on Twitter.

If you liked this, please read our other reviews here and don’t forget to follow us on Twitter or Instagram or like us on Facebook.

I am passionate about screwball comedies from the 1930s and certain actresses from the Golden Age of Hollywood. I’ll aim to review new Netflix releases and write features, so expect a lot of romantic comedies and cult favourites.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.